Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Concrete poetry is not one style but a cluster of possibilities, all falling in the intermedium between semantic poetry, calligraphic and typographic poetry, and sound poetry. It first crystallized out of these earlier modes in the early 1950s in the worst of such people as Eugen Gomringer (Switzerland), Carlo Belloli (Italy), Diter Rot (Iceland), Öyvind Fahlström (Sweden), the Noigandres Group (Haroldo and Augosto Campos, Decio Pignatari and others, all from Brazil), Carlfriedrich Claus (German Democratic Republic), Gerhard Rühm, Friedrich Achleitner and H.C. Artmann (Austria), Daniel Spoerri and Claus Bremer (West Germany), and Emmett Williams (United States then living in West Germany). In recent years a second generation of major figures have added to the movement including such people as Hansjörg Mayer (West Germany), Ladislav Novak and Jirí Kolár (Czechoslovakia), Edwin Morgan and Ian Hamilton Finlay (Scotland), Bob Cobbing (England), bpNichol (Canada), Marry Ellen Solt and Jonathan Williams (United States), Pierre and Ilse Garnier (France), Seiichi Niikuni and Kitasono Katue (Japan) and many others. The very fact of the appearance of parallel work more or less independently in so many nations and languages indicated of the unique aspects of the movement, namely its source being in the development of a new mentality in which values become fused and interrelationships established on a more complex plain than was the case in the purer, earlier modes of poetry.

Emmett Williams, as one of the original practitioners of concrete poetry, has been in a unique position to observe the development of the movement since its beginnings, and the selection in this volume therefore reflects a view of this evolution from within the movement rather than from a distance. However it is far too soon to regard any pathology of Concrete Poetry as being definitive, since the movement is extremely active and major works have yet to appear in this most interesting of current poetry movements.

(From jacket cover)

The source of nearly all of the ideas in Pop Art was Claes Oldenburg’s store, which functioned from 1961 to 1963. After all, didn’t Andy Warhol buy the first Oldenburg’s big blue shirts? But what’s missing from the literature is not the history of the movement, but a direct confrontation with the ideas posed by it. For example, here is an extract from one of Oldenburg’s notebooks of the time: “The fact that the store represents American popular art is only an accident, an accident of my surroundings, my landscape, of the objects which in my daily coming and going my subconsciousness attaches itself to. An art of ideas his a bore and a sentimentality, whether witty or serious or what. I may have things to say about US and many other matters, but in my art I am concerned with perception of reality and composition. Which is the only way that art can really useful - by setting an example of how to use the senses.” These notes, scenarios for happenings (some of which were extremely socially conscious), sketches and projects have been collected together and a selection made by Emmett Williams and Claes Oldenburg. The resulting work is called Store Days, which costs $10 and will be ready by April 15. Most of the ideas that his kind of art is about will have to be revised once this book is ready.

(Dick Higgins, Something Else Newsletter, Vol. 1 No. 5, 1967)

"Emmett Williams' Sweethearts is a breakthrough. It is to concrete poetry as Wuthering Heights is to the English novel; as Guernica is to modern art. Sweethearts is the first large scale lyric masterpiece among the concrete texts, compelling in its emotional scope, readable, a sweetly heartfelt, crying laughing, tender expression of love." - Richard. Hamilton from the jacket cover

As seen on http://www.sweetheartsweetheart.com and created by Mindy Seu

Changes, a look into the working notebooks of Merce Cunningham, is the most comprehensive book on choreography to emerge from new dance. Cunningham’s reflections on his art engage the reader in an awareness of both his own sensibility and the potential of the medium.

Its pages are reproductions of the in-progress notes for the individual dances - to indicate the method - superimposed with speculation - to define the problem - and complemented with visual and other material relevant to the performing arts.

Cunningham approaches the dance in terms of its primary elements - movement in space and time - and the source from which they spring - stillness. He examines the theater in terms of the presence - or absence - of movement, sound, light, decor, and costume. He explores these elements separately, then superimposes them upon each other, and sometimes back upon themselves. He further opens his work to the possibilities inherent in each element through chance, a means of introducing variety into the compositional procedure.

“Although the notes began,” he writes, “as necessary, if inadequate, ways to further choreographic ideas, the use of chance methods demanded some form of visual notation to allow for possibilities. A crude computer in hieroglyphics.”

Cunningham’s ceaseless explorations give his work, as evidenced in this book, a continuing vitality.

(From jacket cover)

Drawings by Marilyn Harris.

One of the zaniest imaginations operating on the off-off-off Broadway scene belongs to Ruth Krauss. This is a delightful selection of her short theater-poems: plays, shows, monologues, horse-opera-with-wings and the like.

(From Dick Higgins, The Arts of the New Mentality: Catalogue 1967-1968, Something Else Press, 1967)

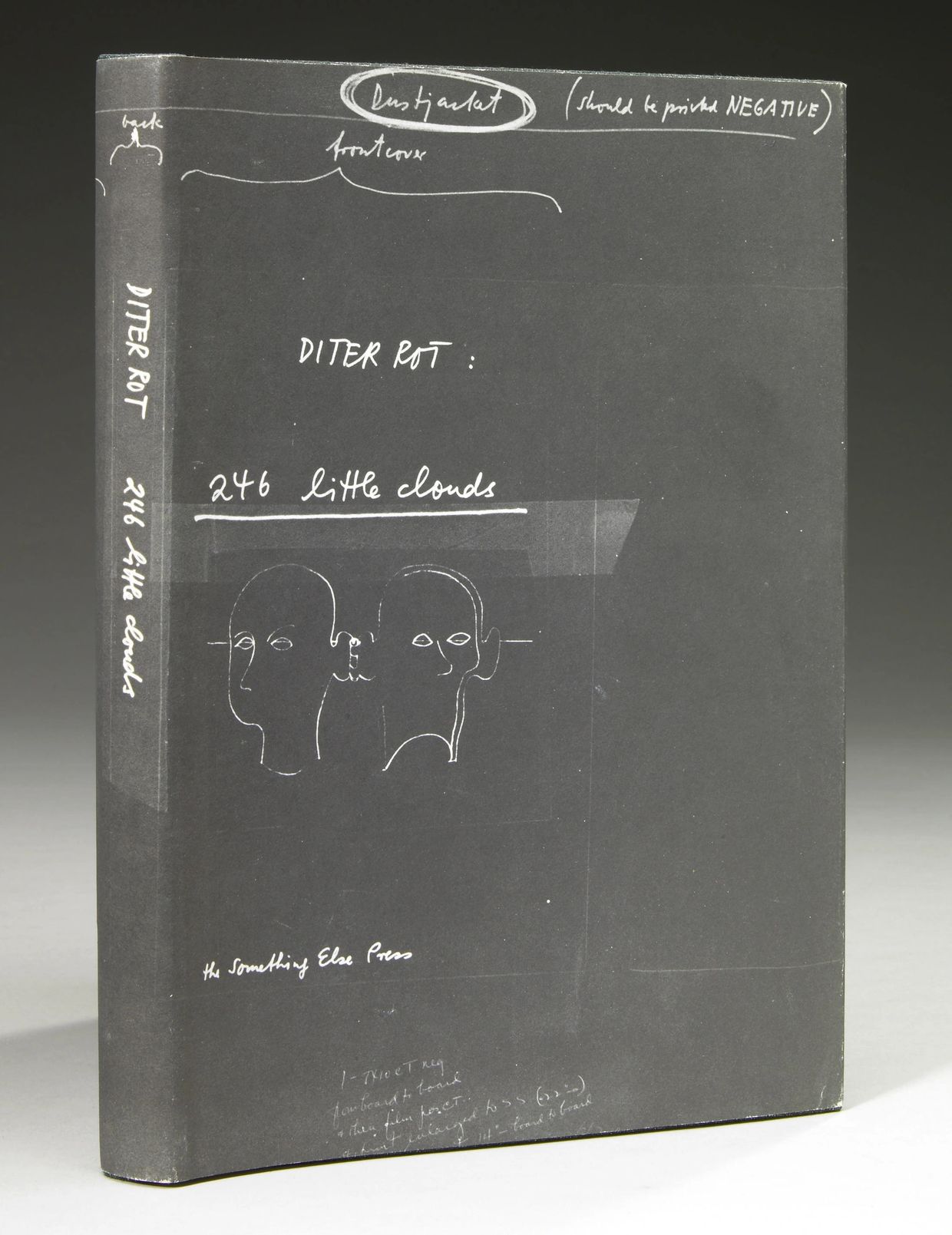

As soon as we start looking in the European avant-garde we keep coming up agains the name, unknown till now in this country except to a few connoisseurs, of Diter Rot. Some artists are one-man movements: but Rot is a multi-movement man. Very little of what is being done in purist design, minimal art, concrete poetry, objects books, the new realism, pop-art, the new pornography, etc., has escaped his influence, as originator, co-originator, etc. The present work is a sort of lyrical diary, simple and personal. If it is, perhaps, less overwhelming than the huge Mundunculum, less “far-out” than the concrete poems, it is also perhaps more accessible and a more suitable introduction to the work of the fascinating Icelandic Swiss chimera. In its own right, however, the Clouds show Rot as a writer, Rot as a visual artists, and Rot as a book designer, and is therefore an appropriate indication of the scope of the man’s work.

(From jacket cover)

Eugen Gomringer is best known as a founder of concrete poetry, which is usually equated, indiscriminately, with all visual poetry and therefore expected to be highly visual. But Gomringer concentrates the visual element of his poems in what I have called elsewhere “geometric structures” of the underlying logic; and the work is therefore not apt to be visually obvious, which is why he has not yet shared in the recent plethora of concrete poetry exhibitions and in its general vogue.

This book is an attempt to make it clear what he has accomplished, what his work really entails. Jerome Rothenberg (one of the best known young poets and the editor (with David Antin) of some/thing as well as of Hawk’s Well Press poetry books), translated this book of his (Rothenberg’s) selections to set the record straight. He chose to concentrate on Gomringer’s Book of Hours, as one of the most lyrical masterpieces of recent years, as well as on a selection from Gomringer’s enormous series called “constellations,” the complete version of which would probably have had to await many years, until that far-off moment when Gomringer no longer is mining this vein, still a very rich lode.

Gomringer considers, more profoundly perhaps than most poets working today, what he does and how he does it. He is, like Anton Webern in the music of the recent past, unwilling to produce the many many works needed to satisfy the demand. In fact, the bulk of his work has, in recent years, been his letters and essays. This combination of un-prolific output and unfashionable willingness to provide his own critical observations no doubt explains why, over all these years since the early 1950’s, he has remained unknown to the English speaking world.

But Gomringer is part of the new Revolution of Meaning which is sweeping the world of poetry, and which implies the new search to provide the most appropriate forms for the new meanings and intentions. So it is with the greatest pride that we present to the English-speaking world, the first book of magnificences by a very greater writer in a very exciting movement, concrete poetry.

(From jacket cover).

With a foreword by Sherwood Anderson, this is easily accessible Stein and in her most characteristic style. Undoubtedly one of her major works, it was originally published in 1922 and was long unavailable until we re-issued it in typographic facsimile. Anybody who would like to sink their teeth into Stein for the first time could hardly do better. And for those already in her work, well, this one shows her wonderful Cezanne-like language in all its shining opacity.

(Dick Higgins and Jan Herman, Catalogue Fall/Winter 1973-1974, Something Else Press, 1973)

Edited with Alison Knowles.

The reading or memorizing of something written in order to play music is an Occidental practice. In the Orient, music by tradition is transmitted from person to person. Teachers of music require that students put no reliance on written material.

Western notations brought about the preservation of ‘music,’ but in doing so encouraged the development not only of standard of compositions and performance, but also of an enjoyment of music that was more or less independent of its sound, placing quality of its organization and expressivity above sound itself.

Furthermore, as the permissions to reprint in this book testify, music, through becoming property, elevated its composers above other musicians, and an art by nature ephemeral became in practice political.

In any case, until recently, notation was the unquestioned path to the experience of music.

At the present time, however, and throughout the world, not only m most popular music but much so-called serious music its produced without recourse to notations. This is in large part the effect of a change from print to electronic technology. One may nowadays repeat music not only by means of printed notes but by means of sound recordings, disc, or tape. One may also compose new music by these same recording means, and by other means: the activation of electric and electronic sound-systems, the programing of computer output of actual sounds, etc. In addition to technological changes, or without employing such changes, one many change one’s mind, experiencing, in the case of theatre (happenings, performance pieces), sounds as the musical effect of actions as they may be perceived in the course of daily life. In none of these cases does notation stand between musician and music nor between music and listener.

Asked to write about notation, André Jolivet made the following remarks: “One hundred and fifty years ago, western musical writing acquired such flexibility, such precision, that music Wass permitted to became the only true international language.”

Fraçois Dufrêne, replying to a request for a manuscript, wrote as follows: “I am not in a situation to give you any kind of score, since the spirit in which I work involved the systematic rejection of all notation….I ‘note’ furthermore that a score could only come about after the fact, and because this loses from my point of view all signficence.”

This book, then, by means of manuscript pages (sometimes showing how a page might leave its composer’s hand in its working form as he used it, sometimes finished work), shows the spectrum in the twentieth century which extends from the continuing dependence on notations to its renunciation.

(From jacket cover)

Of all Gertrude Stein’s major novels Lucy Church Amiably remains one of the least known, in spite of being more accessible than others and more lyrical in tone, because of the mechanical facts of never having been published or widely distributed in an English-speaking country.

In keeping with the policy of the Something Else Press of gradually bringing about a situation in which all of the major works of Gertrude Stein are again available, we have reissued the 1930 Paris edition of this book, which Miss Stein described as “A Novel of Romantic beauty and nature and which Looks Like an Engraving."

(From Dick Higgins, Tomorrow’s Avant Garde…Today: Catalogue 1970, Something Else Press, 1970)

The life, loves, and stock market reports of the “The Proust of Wall Street.” Gutman is on the street, not of the street according to Emmett Williams, and if you open this book you’ll see why. There is Gutman painting in his Provincetown studio and there is Gutman in the bathtub with Lucinda Love’s legs around his neck, and there he is again reading the tickertape in his Wall Street office, and then there’s Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg and G-String Enterprises, and Gregory Corso and David Amram, George Segal and Charlotte Moorman. And let’s not forget the lady wrestlers. The book is a veritable treasure trove of anecdotes and enticements which”…do not constitute an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy.” Take it from there.

(Dick Higgins and Jan Herman, Catalogue Fall/Winter, 1973-1974 Something Else Press, 1973)

Since it’s original publication in 1930, Henry Cowell’s New Musical Resources has become recognized with Arnold Schoenberg’s Structural Functions of Harmony and Paul Hindermith’s The Craft of Musical Composition, as one of the three seminal technical studies by major twentieth century composers. While all three have gone out of print, the Cowell work has been, until now, the most difficult to obtain., owing to the small size of the original edition and he short time it was kept in print.

When it first appeared, New Musical Resources must have seemed incredibly visionary. Both the Schoenberg and the Hindermith works are backward-looking, into the history of harmony, with the proposed developments simply an extension of the past. While the Cowell works is not without its references to history, essentially it looks hardest at the phenomenon of music itself, and explains music in terms of what it is, not in terms of whatever conventions had been dominant in the preceding period. This has been an important characteristic of American musical tradition, from Charles Ives and Carl Ruggles through to John Cage, Earle Brown and Philip Corner.

(From Dick Higgins, Catalogue 1969-1970 Something Else Press, Something Else Press, 1969)

The first multi-track sensibility book. In four columns, the farthest left with big theater experiments, reflecting the author’s background as a founder of happenings. The next column with works in an indefinable forma, natural enough for the author who coined the term “Intermedia.” The next column mostly with experiments in poetry and linguistics, which is a major part of Higgins’ corpus. And on the far right, the little essays occasionally published in the Something Else Newsletter, the clearest and simplest statements of the theory underlying today’s avant-garde, all bound together in a prayer book format in this book with the incredible acrostic title (what it might stand for is given on page 8)

(From Dick Higgins, Something Else Newsletter Vol. 1 No. 12)

Page 8: Freaked Out Electronic Wizards and Other Marvelous Bartenders Who Have No Wings

Copyright © 2021 Estate of Dick Higgins - All Rights Reserved. Republication For any Purposes is strictly forbidden without Permission from estate of Dick Higgins.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.